Cursive in the Digital Age

I've had multiple conversations in recent months where people across generations (including zoomers) have lamented the fact that cursive is no longer taught in schools. That cursive is a valuable part of our culture that we're losing.

They repeatedly cited stylistic analysis for forgery detection as a laudable use, as well as the authority of a signature. “People used to sign their names on documents, your signature notorized it, you were backing it with your name, your integrity. That mattered.”

Of course, signatures are still used, though today it’s more security theater than anything. I spent a couple years delivering pizzas and had to ask for signatures from customers every time someone paid via card. After that, these symbols of integrity were hardly acknowledged again before being tossed in the trash at the end of the day.

I had to sign and initial many documents at an eye appointment the other day, and when subsequently acquiring some new glasses. Despite the fact that automated technology for checking signatures is very possible today - signature authentication could be easier and more widespread than ever - I suspect every signature I provided met a similar fate to those pizza delivery signatures.

Granted, it’s also worth noting that nearly any digital technology for checking signatures could likely be used in reverse, to create arbitrary forgeries. Low-entropy, analog techniques like signatures also lack the sheer security of modern cryptography. Such a modern, digital modernization effort on an old technology would likely still require human witnesses and physical copies if any real security were demanded, not unlike voting. It would necessarily be not just a material and digital technology, but a social technology. Then again, what else can any foundation of trust in society be?

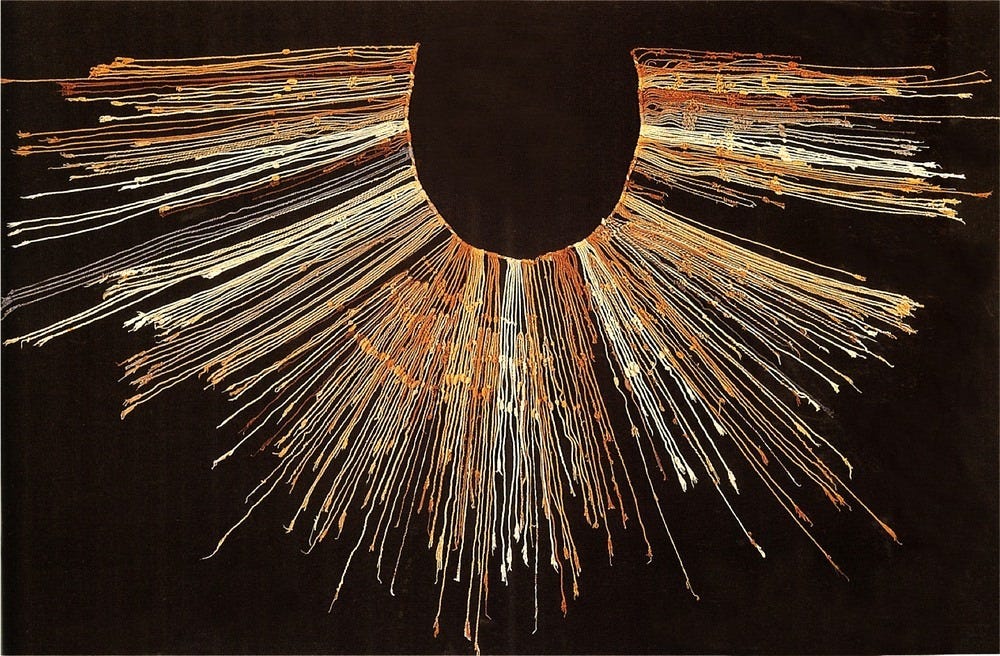

It’s perhaps easy to point out how times have changed. Everything is digital now. However, all this talk of trust, authentification, and signatures, especially in the context of information technology, should not be unfamiliar today. This is the whole purpose of cryptography - to produce a backbone of trust in our digital information technologies. In some sense, we’ve simply swapped curvy penstrokes for curvy mathematical functions, such as the elliptic curve below.

Modern cryptography is, of course, in its early days. While perhaps it hides deep within it some beautiful mathematics, it has yet to find a compelling way to make that beauty visible to common people, and thus lies in far more obscurity than it deserves. Cursive in comparison has had many centuries of maturation.

Perhaps cursive is something that we should keep around for some time, as a reminder of the sheer extent to which humans can create something both so beautiful and so practical. There’s a lot to be admired in these wavy letters.

The Maturation of Information Technologies

Different material technologies have different tradeoffs, and the possibilities lie downstream of these. Cuneiform, especially densely written, is not always easy to read. It is slow to write, having to precisely position and press a wooden wedge into clay at a specific sequence of angles and positions to create a symbol. Once written, it’s not even done; it must be dried and then fired in a kiln.

Of course, if you wanted to place a seal on an object, a form of ancient signature or stamp marking it as yours, having that seal marked in clay and baked into stone is perhaps a very nice feature.

This is an ancient, primitive technology. Things only get better with refinement.

Writing is far from the first information technology. Language itself is of course one too. But language is far from the top of the information technology stack; there are a great deal of complex technologies built on top.

Some animals, such as parrots, can be taught basic human language. Some have even suggested a basic level of understanding. What is much rarer to hear from an animal is serious questions. Humans on the other hand are obsessed with asking questions, even from a very young age.

Asking questions in a discussion form a powerful defensive tool. If I were to declare myself the “Queen of Ireland”, people would have some very hard questions I’d need to answer if I wanted anyone to take such a claim and its consequences seriously.

We can go even further up the stack. One extremely common technology in ancient societies is poetry; verse isn’t just pretty words for the sake of pretty words. By rephrasing language in a way that introduces repetitive structure, we can make it dramatically easier to memorize exactly. How much of this article could you memorize, word-for-word, by just reading through it a few times? Compare that to how quickly you can learn the words to a song. There’s a reason works such as the Illiad, the Odyssey, and the Epic of Gilgamesh take the form of verse.

This technology can be very effective at diminishing the effects of the game of telephone that often arise in passing stories from one person to another. Poetry is an extremely widespread human technology; the aboriginal Australians, isolated from the rest of the world for tens of thousands of years, even memorized vast maps of their continent by converting sequences of landmarks and directions into songs. For them, a journey of a thousand miles started by singing a song.

Tally sticks are also a notable, very ancient technology. The Ishango bone is estimated to be around 20-22,000 years old.

One information technology that I’m rather fond of is the khipu system from Andean cultures. The oldest evidence of khipus goes back nearly 5000 years to the Caral-Supe civilization, making it one of the oldest writing systems.

However, rather than encoding information as images, khipus encode their information in the form of knotted strings. The color, material, twist direction, grouping, spacing, and connectvity of strings encodes information.

Textiles unfortunately do not preserve well under most conditions, much less the firey conditions most were exposed to following Spanish conquest; only around 800-1300 khipus are known to exist today. We know a fair bit about how they were used, and a little of how they worked, but the true breadth of uses that inevitably arise from nearly 5000 years of innovation and creativity is largely lost.

What we do know is utterly astonishing. Khipus served as a currency, a writing system, and an accounting system. The Spanish described its accounting capabilites as so effective that across the entire 6-to-14-million-person Inca empire, larger than the Roman empire at its peak, “not even a pair of sandals could be unaccounted for”.

Khipus encoded information in a hierarchical format that is in many ways comparable to modern JSON, albeit made from real string. In addition to the tree-like structure however, khipus also made heavy use of checksums. These checksums, in combination with social protocols that involved creating and distributing many copies of each khipu, resulted in an accounting system that in many ways echoed the workings of modern cryptocurrencies.

There is even evidence that the Incas had developed something very close to double-entry accounting, likely around the same time this revolutionary accounting system was also invented in Europe.

While proper khipus often required significant training to interpret, many people kept personal khipus as something akin to an ID card. Khipus were considered so important people were often buried with them (this is how some surviving khipus have been found). Farmers in places like Peru still use khipus for keeping track of their livestock.

However, you don’t just find the practical side of khipus. Some khipus weave the strings together into a patterned fabric. Some khipus are considered “narrative khipus”, which Spanish accounts describe as recording songs, poetry, letters, stories, and history. Khipus could be rolled up for easier storage and transport, but could also be worn as almost a form of clothing. Khipus weren’t just a currency, a writing system, and an accounting system all rolled into one; they were also an art form.

Many traditions surrounding khipus associated them closely with different parts of the body, and there are reasons to believe some of the structure of khipus were associated with certain patterns in the organization of Incan society as a whole. Khipus were not just able to be read by sight, but by touch as well. In fact, important information was encoded by which specific plant fiber or animal fur the string was made from, which often was much easier determined by touch than by sight. Different knot types were also often easier distinguished by touch. The Inca lauded this as a feature, not a bug, arguing that the deepest knowledge could only be gained through multisensory learning.

These are not signs of some mere ordinary, simple technology. This was something far greater, something that matured over thousands of years into a tool to fill a wide range of niches, both practical and artistic, often both at once.

The Beauty of Cursive

Cursive is the rich, matured form of the handwritten word.

The symbols that formed the English alphabet came from the Latin alphabet, which was derived from Greek, derived from Phoenecian, derived from Egyptian hieroglyphs, likely derived from even earlier froms of proto-writing. The legacy of this system traces back many thousands of years. When you write down an A, you’re drawing the heavily refined and simplified form of what once was an image of a bull’s head and horns (flip the page upside down if you don’t see it).

Over time, the symbols became fewer, simplified, easier to draw, easier to recognize, easier to learn, and more closely associated with phonetic sounds rather than the original complex logograph system that often bordered on a cryptic game of charades.

As literacy became more widespread, written documents became longer, paper became smoother, and pens were developed and then became easier to use, the sharp angles and blocky text of early alphabets began to transition into smooth, continuous curves. Cursive.

Cursive is in one sense optimized for speed of writing, but it’s also in some sense optimized for stylistic expression; there’s a great deal of flexibility provided in the representation of letters, and plenty of room for variation in curvature and stroke length. When handwritten, this produces a signature style, a product of the interaction between the things going on deep inside the writer’s mind and in the system of nerves, muscles, bones, skin, pen, ink, and paper.

Humans think with their tools, as their tools constrain what is and isn’t possible, and decide which actions are easiest. The constraints of the tool and its artistic expression influences the thoughts going into writing. Friedrich Nietzsche, upon abandoning handwriting in favor of a typewriter, found that his entire writing style changed. Much like khipus, cursive is multisensory, even if just during the writing process.

Cursive creates room for artistic expression and calligraphy, but it also creates room for cryptographic functionality, as the precise patterns of an individual’s handwriting can often be much easier to differentiate than to replicate. Forgeries are possible, but difficult. Convincing forgeries are far harder, especially when confronted by a trained eye.

From such cryptographic primitives, protocols of trust can be constructed. Upon such protocols, personal relationships, organizations, businesses, industries, and eventually entire functional and competent cultures can grow. Cursive is certainly far from the only one involved, but it historically has served a valuable role.

Cursive is a beautiful blending of culture, art, biomechanics, efficiency, material and social technologies. Inventing something from scratch that simultaneously blends so many features so well is astonishingly hard, really only possible through centuries of refinement.

Calling it an invention or technology in any traditional sense gives far too much credit to individual achievement. If anything, we need a new category for technologies that are so mature.

The Legacy of Cursive

Even if cursive is little more than an artifact of a long-gone age, with little modern practical utility, we should keep it around for a while. If not for its utility, as an example of tool that has aged like a fine wine, as a reminder and as inspiration to show us what can be possible.

We should keep in mind that our digital tools, as advanced as they are, are still in their earliest days. In many ways, they are still remarkably primitive and unrefined.

We should, however, not view cursive as some insurmountable achievement, but as a challenge. It is a remarkably well-refined technology. A truly beautiful technology. If we were to achieve a similar level of beauty and maturation in our digital tools, what would they look like? Will Python or Lisp code really still be the pinaccle of software beauty 5,000 years from now?

And perhaps we can look for inspiration as well in parallel systems. Khipus, as noted, share much in common with many modern computing systems. There is a great deal that is still not understood about khipus; perhaps from more deeply studying them, we can find wisdom and hints for how to mature our existing computing tools, provided by an ancient technology that blazed a similar path for far longer.

Thank you for reading this Bzogramming article. I’m working on exploring unusual ideas in an effort to push computing in a better direction. I consider it important to look for a greater context that offers more grand options for building the future. If you want to suport this effort and see where I take the ideas in this article, I hope you’ll consider sharing and subscribing.