New Algorithms, Not New Particles

There is a common idea passed around in tech circles that technological innovation of the 20th century was driven primarily by theoretical physics, and after this began to stagnate – usually blamed on a plethora of boogeymen from a vague time period around the 70s or 80s – all technology beyond computing also began to stagnate. Very often, people insist that we can’t have real innovation again until we start discovering new particles and forces again, and lament that we perhaps have very few particles left to discover.

However, when we dig a little closer and start asking some very basic physics-oriented questions, this narrative falls apart completely.

The vast majority of technology today is based on manipulating atoms, electrons, and photons. We get a fraction of our energy from splitting atoms with neutrons, though far less than we reasonably should for a technology we’ve used since the 1940s, and on very rare occasions we’ll use neutrons for imaging and some other niche uses. Even more rarely we will make use of exotic particles like muons and positrons, mostly for other types of imaging. Muons (heavy electrons) are sometimes used for imaging the 3D structure of rock formations or pyramids, though they are sufficiently difficult to produce that we rely almost entirely on the tiny quantity that the sun generates naturally rather than using more reliable engineered muon sources. Positrons (anti-electrons) are also occasionally used in medical scanners, and are mostly a byproduct of the decay of specific nuclear isotopes, one of the other applications of neutrons.

We may have discovered photons, six different types of quarks, eight different types of gluons, three types of electrons, three types of neutrinos, the W+, W-, and Z0 bosons, a wide variety of antiparticles, as well as the Higgs boson, but the vast majority of this is profoundly useless to us. Will discovering more particles make any difference? If we look at what makes atoms, electrons, and photons so practically useful, it’s that they are abundant and easy to build things with. Humans have been able to manipulate all of these things, at least indirectly, since the dawn of time. Everything else is difficult to interact with, and many of these things can only just barely be clumsily poked at with giga-electronvolt particle accelerators. We’ve understood quarks for 60 years, but there are still no “quark-gluon engineers” and it’s extremely unlikely that such a title will be meaningful even in another 600 years. Even if we can poke at such systems, it takes such vast amounts of energy to have such tiny and unpredictable effects that any useful engineering is unfathomable with any technology we can reasonably conceive of.

Muons were discovered in 1936, positrons in 1932, and neutrons in 1920. The fact that neutrons could trigger nuclear fission wasn’t discovered until 1938, a discovery which promptly kicked off the Manhattan Project. It would not at all be inaccurate to say that “discovering new particles” stopped being a driver of new technological progress after the 1930s, rather than the 70s or 80s.

We know that there are likely additional particles that we have yet to discover – dark matter, gravitons maybe, X17, sterile neutrinos, and perhaps something driving dark energy. However, the reason we haven’t discovered these is because they interact absurdly weakly with anything that we do know how to build – so weakly that for most of these we have never measured any obvious interaction with anything that we’ve ever built. We can only measure their very indirect effects by observing places where astronomical measurements don’t line up with our mathematical models, or spotting a few other very minor discrepancies at absurdly high energies. If your goal is to engineer useful things with these as your building blocks, this is the last property you’d ever want to have!

Our technology is overwhelmingly built with atoms, electrons, and photons. We have largely the same building blocks that our ancestors thousands of years ago had. Chemistry (or alchemy) is just mixing atoms in ways that rearranges their electrons to bond them together differently. “Discovering new particles” is a blatantly false description of what drove the past couple centuries of progress. Upon closer inspection, much of what drove material innovation was downstream from math – Newton building a much more powerful toolbox to model dynamical systems and geometry, followed by more detailed models of the tiniest components of the universe.

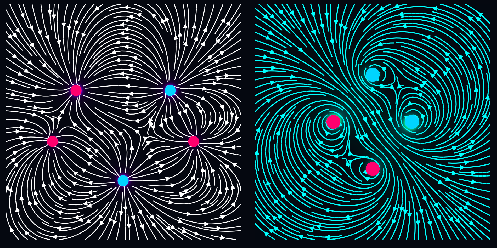

Humans have been aware of electricity in some form since we first glimpsed a thunderstorm or gotten a static shock. Occasional magnetic properties of meteorites were known in ancient times, and medieval monks like Petrus Peregrinus de Maricourt even were studying magnets intensely at least as far back as the 1200s. Benjamin Franklin famously experimented with electricity in the 1700s, but it wasn’t until the mathematical work of Faraday and Maxwell that electromagnetism really became something usable for serious engineering. Once a mathematical theory was in place however, it rapidly exploded into telegraphs, motors, radio, light bulbs, tesla coils, a plethora of vacuum tubes, cameras, the television, and more. It wasn’t until 1897, a couple decades into this technological revolution, that a particle called the electron was even confirmed to exist.

The existence of atoms and the theory of chemistry were increasingly fleshed out throughout the 1700s and 1800s, and many practical heuristics and principles were understood decades before any of their component particles were discovered. What enabled advanced chemistry wasn’t so much the discovery of protons and electrons, but the quantum theory that allowed us to accurately model their behavior. Even then, there is a lot of talk today about “quantum chemistry”; even though we have the equations to describe everything, we’re mostly confined to chemistry where interactions are simple and easy to compute. The vast majority of chemistry is much more complex, and the computations required to apply our equations to answer even the most basic of questions are so complex that people are concerned that we may only be able to answer them with quantum computers.

The ancient, classical world saw a substantial degree of technological progress too, and while today we may be hesitant to compare its magnitude to the industrial revolution, they did understand the principle of steam engines, were capable of manufacturing billions of standardized glass and clay pots, and even made use of water wheels, screw pumps, and complex bronze gearboxes. Vetruvius’ “De Architectura”, written in the first century BC, laments how underutilized water wheels were. This book appears to have had an impact, as archaeology suggests that water wheels became much more common in Rome over the following few centuries. We do not have any textual references to the extremely elaborate Antikythera mechanism, though surviving texts make casual references to enough bronze gearbox mechanisms like wagon odometers in the later Roman empire that, provided a time machine, the couple centuries after Christ may have looked to modern people as slightly steampunk. This is an impressive degree of technological progress to be made without discovering any new particles! Much of this progress is most likely the product of advances in geometry and mechanics, as well as the collection and centralization of knowledge from across the ancient world in vast libraries like the one in Alexandria.

Semiconductors and Condensed Matter Physics

Semiconductors are not exotic magic. Conductors are materials where the uppermost filled (valence) electron orbitals are very close or overlapping with additional, empty (conductance) orbitals where they can move more freely. Insulators generally have a very large “band gap” separating these orbitals, requiring a large amount of energy to be pumped into electrons to get them to jump from the valence to the conductance band. Other factors such as heat, light, and electrical fields can also affect the size of the band gap or how much energy electrons have available to try jumping it. If you simply ask “what happens if I have a material with a band gap large enough that it’s an insulator by default, but small enough that these other factors can temporarily change that?” the medium-sized-band-gap materials you end up with are semiconductors.

Semiconductors are also all around you. Most optical properties of objects are a combination of band-gap-like electron-photon interactions and scattering effects. What makes glass transparent is its band gap of 9eV; no photon of visible light (1.8-3.1eV) is capable of exciting its electrons to the conductance band, so they simply pass right through. Silicon has a band gap of 1.1eV; visible photons interact with it and can be absorbed and re-emitted making it opaque and shiny, while it is transparent to infrared light below 1.1eV. Band gaps within the visible range can create a variety of colors. Organic molecules often have more complicated electron structures, and so talking of band gaps and semiconductors there is more of an analogy, but it’s still just molecule-scale photon-electron interactions driving macroscopic coloring.

Band gaps and their more complicated organic cousins have been the underlying mechanism behind many manmade pigments for thousands of years. One such organic cousin is porphyrin, a core component of both hemoglobin and chlorophyll, and some of its behavior can be understood as a kind of semiconductor. It becomes chlorophyll when doped with magnesium, and heme when doped with iron.

Silicon isn’t some rare, special material. It’s just abundant, easy to work with, and has other reasonably nice properties, but there are many other semiconducting materials out there. I recall a conversation once with a semiconductor engineer who remarked that he considered the luckiest bit of any of this to be that silicon and silicon dioxide (glass) happen to bond together very nicely, making it very easy to engineer circuits with silicon while having good insulation between the wiring without huge engineering headaches from getting the different crystal lattices to stick to each other.

Semiconductors are not some exotic “top of the tech tree” material; they’re actually one of the first unexpected things you’d expect a civilization to discover once there is a basic understanding of quantum mechanics and conductivity, only to discover that it has actually been ubiquitous for eons. A wide variety of materials all around us have wonderful properties we never before dreamed of! We should actually expect many other bizarre materials with strange, emergent quantum properties to be found further along the tech tree, should we go looking for them. Known examples include superconductors and scintillators. The field exploring emergent quantum properties of materials is Condensed Matter Physics (the name is misleading, and really just refers to the study of emergent properties in large numbers of atoms), and it is still one of the newer branches of physics and rarely wins serious attention or Nobel Prizes despite its practical value. It however also seems to have a relatively limited toolbox for understanding the materials it studies, very often resorting to describing emergent quasiparticles and reasoning about their behavior with little more than fluid dynamics analogies.

Bits Hiding in the Atoms

There certainly are many problems which boil down to producing large quantities of some physical thing – specific chemicals and materials, heat, light, energy, etc. – and accomplishing each of these requires some ability to harness certain degrees of freedom in physics. The vast majority of problems however, as well as the implementations of methods for producing these physical things, are better understood as composing a small variety of these interactions in very elaborate ways rather than the simple prodding of a large variety of orthogonal fundamental forces.

We can consider new particles and forces of nature to perhaps give us new degrees of freedom for interacting with the world, but there is almost never any genuine need to use anything other than atoms, electrons, and photons. On rare occasions we will work up the courage to make some cheap energy using neutrons, and on far rarer occasions we will do some exotic metrology with muons and positrons, which are really no more than fancy cousins of the electron with different masses and charges. Everything else is a billion-dollar science experiment.

The problem of arranging some very complicated system which can coordinate a small number of physics interactions is fundamentally a matter of building something with the right behavior, that performs a correct and specific function, and this is fundamentally a computational problem no matter how many layers of indirection and denial we pile on top.

The actual future of technological innovation is not in finding new degrees of freedom, but in finding more powerful and useful systems which we can build from these primitives. Atoms, electrons, and photons are already Turing-complete and can send signals back and forth at the speed of light. Beyond nuclear power and a few rare, niche applications of exotic particles, what else do we genuinely need? We don’t need to dig deeper and break things into smaller pieces – the path forward is to take these component pieces and build bigger and stranger things with them than we ever dreamed of before.

The Library of Babel is infinite, and though most of it is gibberish it still hides unfathomable quantities of valuable things. The number of possible 32-byte programs is greater than the number of atoms in the observable universe. The number of 1000-line-of-code programs is for most practical purposes infinite, and we should expect that there will still be a steady stream of breakthroughs from novel ~1000-loc programs, algorithms, and theorems creating breakthroughs a million years from now. The most revolutionary technologies that the future holds are to be found among the unknown unknowns. We only bring these things closer to the known by expanding our imagination, by finding new organizing principles, new mathematical tools, new patterns in the world, new ways of thinking, new possibilities. The fact that so much of our science fiction and futurist art is retrofuturist, or that the most inspiring vision of the future of computing people can point to is Snow Crash or The Sovereign Individual, with the past 30 years of surprises that the internet has wrought failing to inspire compelling alternatives, are strong signals that it is our imagination that is failing us, not our ingenuity.

We have some leads. Machine learning has made a substantial and growing impact over the past 15 years. Faced with many problems which we do not know how to engineer directly, we now have a tool which can synthesize solutions using methods that large teams of interpretability researchers are only beginning to scratch the surface of. This works as long as we can craft a sufficient dataset, a viable neural net architecture, and provide a sufficiently vast amount of raw compute. Many things that we did not previously know how to build can now be built – and it would be of far greater value if we better understood how these things worked, were able to engineer them with more control, and better understood their capabilities and limitations.

The array of equillibrium states of a physical system is NP-complete. Nondeterministic (NP) computations are very useful for many constraint and optimization problems which are ubiquitous across science, physics, and engineering, but they are also difficult and expensive to compute. They do however contain a great deal of structure, which for a wide array of problems makes them easier to solve in practice. Much of the field of cryptography is focused on building systems with these kinds of properties which are not accidentally easier to break than we intend them to be. However, if we carefully construct a physical system structured in the right way, and we allow it to settle to a stable point, we can expect its final configuration to encode a solution to our problem.

On one hand we can lament that this makes physical systems hard to predict and model, but on the other hand we can celebrate that the universe gives us a physical substrate for computing many very useful problems which would otherwise be prohibitively difficult to compute. Sometimes a problem is just too difficult though, and we may run out of energy or time before the solution we want is reached, that Avogadro’s number of atoms is an insufficient number of FLOPS, and a better understanding of how nondeterministic computation behaves would enable us to optimize this, as well as potentially better understand when a proper solution is and is not attainable.

This also includes the chemical systems inside of cells. A point I’ve been trying to make to biology people (and that I’d like to figure out how to express more clearly) is that many of the problems biology constantly needs to solve are NP-complete, and that this simple fact about equilibria implies that DNA can simply encode a shockingly tiny number genes defining a few constraints, and that allowing the resulting biochemicals to react and settle would be able to solve a wide range of arbitrary constraint or optimization problems defined by these chemical constraints. If natural selection is just fumbling around design space randomly, and these systems are so absurdly useful and simple, we should be absolutely astonished if biology isn’t making use of them for nearly everything. The difficulty of computing these problems however means that programmers and researchers often avoid them like the plague and neglect studying them – however if every single chemical reaction counts as a computation, and a single cell may include billions or trillions of reactions per second, then we should expect biology to have extremely easy access to a shockingly powerful and useful set of computational primitives. A single cell would have comparable computing power to an entire laptop.

There additionally are many very nice properties of how these constraint systems compose that suggest very compelling answers to difficult questions of how extremely complex systems can evolve incrementally! This may also make them easier to engineer, if we simply understand the principles and build the right tools. I fully expect that if we had a few more polymaths crossing these domains, and if we managed to get more people to develop tools for reasoning about Nondeterministic computation, that we’d build out a mathematical toolbox that would at a bare minimum do for biology what calculus did for physics. Even if you can’t measure every variable within a physical system, the principles behind calculus and classical mechanics are enough to place constraints on what is and isn’t possible that otherwise would not be obvious.

And of course, this is to say nothing of applications beyond biology; this nondeterministic computation arises in all physical systems, and we should expect that many physical systems which we struggle to understand today will yield to a better toolbox. And even then, this is merely a known unknown.

As we push harder toward the physical limits of computation, computer science will necessarily need to account for the physical embedding of computation in space and time, its use of energy, its reversibility, and more. Ideas from physics will increasingly make their way into computing. Likewise, ideas will work their way back, and it will increasingly be possible to describe properties of physical systems as decision functions within certain complexity classes, or perhaps some richer descendant of this classification. It’s worth remembering that Big-O notation is really just a kind of Taylor Series.

The past six months I’ve been living in San Francisco trying to get my startup off the ground. Something about this has diminished my ability to write, but I am working my way back into the habit of writing and have several more essays in the pipeline. I wish everyone a Happy New Year!